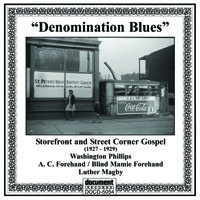

Washington Phillips - Storefront and Street Gospel

Storefront and Street Corner Gospel

In December 2002, after long and diligent research, Michael Corcoran, a music writer for the ‘American Statesman’, of Austin, Texas, published his findings regarding George Washington Phillips. His search revealed that the singer, more familiarly known as "Wash", was born somewhere in Texas on 11 January 1880, the son of Texan, Nancy Cooper and Tim Phillips from Mississippi. However, according to the 1920 and 1930 census data, Phillips places his birth at the later date of c. 1892.

His occupation was listed as “Farmer, General Farm” with property sited in Freestone County, Texas, and his wife, Electra, was recorded as having been born in Texas in 1900. In December 1927 a mobile recording unit of Columbia Records, under the direction of Frank B. Walker, was set up in a makeshift studio in Dallas, Texas. The object was to record local artists who had been traced via advertising articles in the local press. Phillips first recorded track was 'Mother’s Last Word To Her Son', which produced a companion piece, 'A Mother’s Last Word To Her Daughter', during his final session in 1929. The gently swinging sixteen bar song with its “aabb” rhyming-scheme is his own composition, while 'Take Your Burden To The Lord' was composed by Charles Albert Tindley. 'Paul And Silas In Jail' retells the Biblical story and balances “the place they call heaven” against “Sugarland”, the notorious Texas state penitentiary. On 'Lift Him Up That’s All', which retells the story of the woman at Jacob’s well, the lead-in and the coda both differ from the melody of the song itself. 'Denomination Blues' is Phillips’ most impressive recording; in Part One six different black denominations are mockingly criticized, while Part Two ridicules their preachers.

'I Am Born To Preach The Gospel' illustrates the argument that “educated preachers are walkin’ around spiritually dead’ by recalling the story of the “educated fool” Nicodemus. 'Train Your Child' is a real oddity being a monologue about the education of children. The lesson is taken from Solomon’s Proverbs and is followed by a particularly interesting solo on Phillips’s “novelty instrument”. 'Jesus Is My Friend' is the plaintive nineteenth century hymn “What A Friend We Have In Jesus,” and is also preceded by a brief explanatory monologue. 'What Are They Doing In Heaven Today?' is another Tindley composition and the aforementioned “A Mother’s Last Word To Her Daughter” uses the chorus of “Bye And Bye, I’m Going To See The King”. The words do not fit the melody very well and the omission of the chorus after the last two verses further adds to the surprises of the arrangement. 'I’ve Got The Key To The Kingdom' is the story of Daniel in the lions’ den, the accompaniment consisting of one chord sometimes enriched by a sixth or ninth note. 'You Can’t Stop A Tattler - Part 1' remained un-issued for fifty years. The song has a humming chorus but the “novelty instrument” sounds less clear. While the first part of “You Can’t Stop A Tattler” condemns gossipers, the second part attacks adultery. 'I Had A Good Father And Mother' is remarkable because of its falsetto and its humming. 'The Church Needs Good Deacons' paraphrases Paul’s letter to Timothy to give an example of a “good deacon” should aspire to be. Especially noticeable in his last four recordings is the fact that the vocal and instrumental parts start simultaneously, proving that Phillips was very familiar with the pitch of his instrument. Although nominally favoring the sixteen bar scheme, Phillips often shortens his bars, which also indicates that he is accompanying himself.

Record sales dropped dramatically in the wake of the Wall Street Crash, and Phillips, like so many other artists was never recorded again, his 1929 records being the rarest of all his output. After his brief period of recording Phillips returned to farming in the black settlement of Simsboro, sixty miles east of Waco, where he owned thirty to forty acres of land. During the week Phillips looked like a farmhand, but on Sunday he donned his best suit, so people remembered both the farmer and the preacher. Virgil Keeton, who sang in a gospel quartet, reminisced: “He used to live in Simsboro with his mother, my aunt Nancy. He used to play this harplike instrument that he made himself. Sang like a bird, man.” Keeton, who was born in 1920, saw Phillips in the mid-thirties and visited him and his mother Nancy regularly. Ex Simsboro resident Doris Foreman Nealy said that Phillips was a “jack-leg preacher,” thereby confirming what Paul Oliver had suspected many years ago. When he wrote, “Jack-leg preachers were an important feature of religious life in the lower economic groups. Generally associated with the Sanctified Movement they sometimes attended regular services of the churches, seeking a chance to preach. More often they addressed spontaneous congregations in the streets or endeavoured to start small store-front churches of their own. Ordination was not important; the call to preach was. "Doris remembered that he didn't have a church, so he'd kinda roam the town looking for some place to preach. In Simsboro, we had a big picnic every June 19, and Mr. Wash would always start it off with a song. But none of us kids knew he ever made any records.”

He belonged to the Pleasant Hill Trinity Baptist Church in Simsboro, but May Nella Palmore, 82, of Teague recalled Phillips also preached and performed at the sanctified St. Paul Church Of God in Christ. “His singing really fit in with that crowd,” she said. “He had such a strong, powerful voice.” The Keetons said they last saw him doing the devotion at St. James Methodist Church in Teague. “I am born to preach the gospel,” he used to say, “and I sure do love my job.” Sixty-two-year old Durden Dixon is one of the few black people still living in Simsboro. From 1944 to 1954 Dixon lived down the road from the man he described as “kind of a hermit.” Sometimes the old man would bellow to drive neighbourhood boys away from his dewberry bushes, while at other time he’d invite them up to his porch, where he’d sing and strum a boxlike instrument Dixon said the man had made “from the insides of a piano.” When Corcoran played him “A Mother’s Last Word to Her Daughter” Dixon remembered Phillips used to sing the song. Phillips used to sing a secular song to Dixon’s mother, called “Won’t You Be My Tater Gal?” Dixon says Phillips was married to a light-skinned black woman named Marie at the time of his death. He kept on playing for neighbours and churchgoers until 20 September 1954 when he died at age 74 of head injuries suffered from a fall down the stairs at the welfare office in nearby Teague. The shack is now gone, but in the sand Corcoran still found Phillips’ old snuff bottle! Washington Phillips now lies in an unmarked grave in the Cotton Gin Cemetery in the countryside six miles west of Teague, an extremely racist community at the time where black history is virtually non-existent.

In 1983 Lynn Abbott discovered a photograph and a drawing of Washington Phiffips. The photo is the size of a postage stamp and was found in an issue of the Louisiana Weekly, dated a week before the release of Phillips’ first 78. The photo shows Phillips holding two stringed instruments. Two other photos, from 1927 and 1950, clearly show the same man. The shape of the head, the little moustache, the nose with its shining tip and especially the characteristic heavy bags next to the base of the nose are clearly identical.

From the above interviews it also becomes clear that Phillips experimented with various homemade instruments. However, none of the above informants saw him play in the recording studio. The Columbia executive who gave Paul Oliver the name “dulceola” did. Musical evidence outlined in these notes and experiments with restored dolceolas have convinced me that the recordings were made with a dolceola. Is Paul Oliver’s “dulceola” simply a spelling error? Or did Phillips call his dolceola a dulceola when he had tuned it from E-flat (the standard tuning) to F (the key of all the recordings)? It all seemed so easy when the dolceola was discovered, but when the Phillips photo turned up the mystery deepened. In his hands Phillips holds two different stringed instruments, without the keyboard which is attached to the dulceola, and neither of them in the shape of a dolceola: they both have a sharp point which is definitely not to be found on the dolceola.

Zithers are distinguished from dulcimers by their having a fretted fingerboard over which some - in certain cases all - of the strings run.The melody is played on the fingerboard strings which are stopped with the left hand and struck with the thumb and forefinger of the right. Beyond these strings are a number of free strings on which the remaining fingers of the right hand make an accompaniment. As the fretted fingerboard is to be seen on the instrument Phillips holds in his right hand it is probably a zither. The instrument in his left may be a dulcimer, different in shape from the dolceola. The dulcimer in the left hand probably has groups of three strings for the chords, with bass strings in between. The left part is for the melody strings. The instruments Phillips holds in his hands cannot be matched with a dolceola keyboard, it simply would not fit. So he probably played these instruments with a plectrum and/or his fingers. This would result in differences in volume and attack. What do we hear on Phillips records? Volume and attack are constant. There is a regular bass. There are embellishments within the chord. There is a long sustain. No special attack can be heard and all the recorded songs are in F; this all points to the dolceola.

In the final analysis I would suggest that in spite of the photograph with the zither and the dulcimer Phillips played a dolceola on his records. This is borne out by the sound of the accompaniment and by the phrases novelty instrument’ on the labels and “an instrument never before used!! in the advert for Columbia 14277. if Phillips had accompanied himself on a zither or a dulcimer, phrases like these would not have been used.

A.C. Forehand

Left-handed guitarist Elder Ma (“AC.” or “Asey”) Forehand was born in Columbus, Georgia, on 9 August 1890 (according to his second wife) or 1893 (according to the Social Security Death index). He lost his sight in 1904 and his first wife, Mamie, who is said to have been born on 8 June 1895, was also blind. During the 1920 census, when the couple were residing in Birmingham, Alabama, A.C. gave his age as 29 (which would make 1890 more likely) and his occupation as “none.” Mamie was registered as being twenty-three and their daughter Rideth Mae as three years and one month. All had been born in Alabama. On 25 February 1927 they recorded 'Mother’s Prayer' and 'I’m So Glad Today' for Victor. A.C. played guitar and harmonica, while his wife, “Blind Mamie Forehand”, accompanied him on triangle, (although discography mentions “finger cymbals”). Three days later Mamie made two recordings under her own name:

'Honey In The Rock', written by the composer F.A Graves, and 'Wouldn’t Mind Dying If Dying Was All'. Her triangle was there again and A.C. accompanied her on guitar. Around 1930 the couple moved to Memphis, Tennessee. In 1936, following Mamie’s death, Asa married his second wife, Frances Forest. She was a blind pianist and organist born in New Orleans on 5 July 1920. In the sixties the couple was active in the Church Of God In Christ. Asa Forehand died on 9 May 1972 and was buried without a headstone at Rose Hill Cemetery. A week later, Bob Eagle interviewed Frances for Living Blues 9. Steve LaVere acquired Asa’s cheap guitar, which was in poor condition and harboured some dead roaches.

Luther Magby

Luther Martin Magby was born on 5 June 1896. During the 1920 census he was residing on a farm in Greenville County, South Carolina. He was aged 22, and his occupation was given as "Farmer, General Farm”. His wife was shown as Mamie 'G' (or similar), also aged 22, and their son was Luther C. Magby, aged 1 year and some months. All had been born in South Carolina. On 11 November 1927 he recorded two songs for Columbia in Atlanta, Georgia: 'Blessed Are the Poor in Spirit' and 'Jesus Is Getting Us Ready for the Great Day'. Magby’s odd pronunciation, his pumping harinonium and the propulsive tambourine result In one of the most compelling gospel records ever waxed. He died on 10 November 1966 in Hartley County, although his residence was given as Dalhart, Dallam County, Texas 79022.

Guido van Rijn.

© 2003 Document Records Ltd

Click here to buy Washington Phillips